Hopecraft

Do I start with frustration or with wonder?

Manifold thoughts on this matter linger in the ether. This is my way to nail them down and develop them. I don’t think I’ll turn the tides of any literary or marketing throes, but I need to write this out.

The Big Idea: Fantasy as a genre, despite its upheld popularity, is rarely allowed to blossom into its true form. These shackles must be released, and fantasy must be sown and reared into its fullest strength.

My fantastical imagination awoke circa 1990 when my dad brought home a set of VHS tapes and asked something along the lines of, “Which should we start with? The Hobbit or The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe?” He was referring to the 1977 Rankin-Bass animated Hobbit and the 1988 BBC production of the first Narnia book. I had no idea what he was opening up to me, but vagueness hinted at in Gummi Bears, Teddy Ruxbin, and Duck Tales all sprang to full life in my mind. No longer was I guessing at what fairy-tale magic, wizards, talking animals, enchanting cities, and other unreal realities the cheap animation of the late 20th century were referring to. I was getting at a primary source.

My fantastical imagination awoke circa 1990 when my dad brought home a set of VHS tapes and asked something along the lines of, “Which should we start with? The Hobbit or The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe?”... I was getting at a primary source.

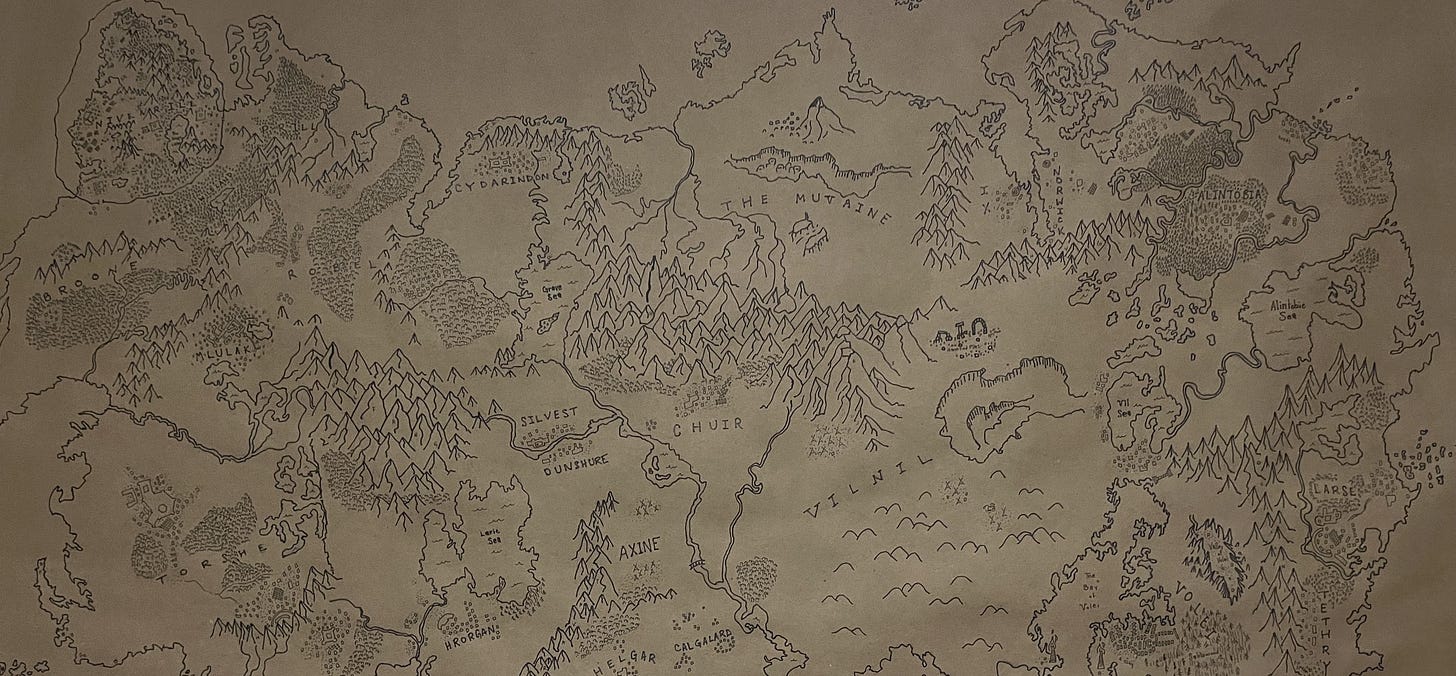

The human imagination is a vast and powerful landscape, and the fantasy genre is a wonderful map to such a frontier. I have roamed it for many a year, notwithstanding drudging fantasy sabbaticals scattered here and there in ignorant times where I thought that “realistic” was more important than “real.” I have other literary and like loves: Westerns, Lovecraftian monster stories, hardboiled detective tales, hearty science fiction, and linguistics, to name a few. But I keep coming back to fantasy for its untold potential.

Where do I start, though? With frustration, or with wonder? My first instinct is to spew my misgivings about the current fantasy market trappings: the thinly veiled nihilism or trashy romance, the relentless aping or appeals to novelty, the subversions and tropes. The postmodern, self-referential chains are weighing the genre down, and every time I read something about, “Let’s move on from Eurocentric castles and forest settings,” “It’s time for men to fade into the background,” or “Enemies to lovers,” I lose faith, as if fantasy were a sum of its parts.

Too many books hold small stories with alien stakes. Too often power fantasies leave me cold and bitter because I can’t root for any of their small, acid, shallow, greedy heroes, or because the good men and women in the story get killed off because “That’s life, folks. Suck it up.” Too often readers settle for lackluster tales of envy, revenge, lurid lust, shock, and titillation, which grip them with raptors’ talons but tear through the flesh only to leave them plummeting to the rocky death of spectacle far below.

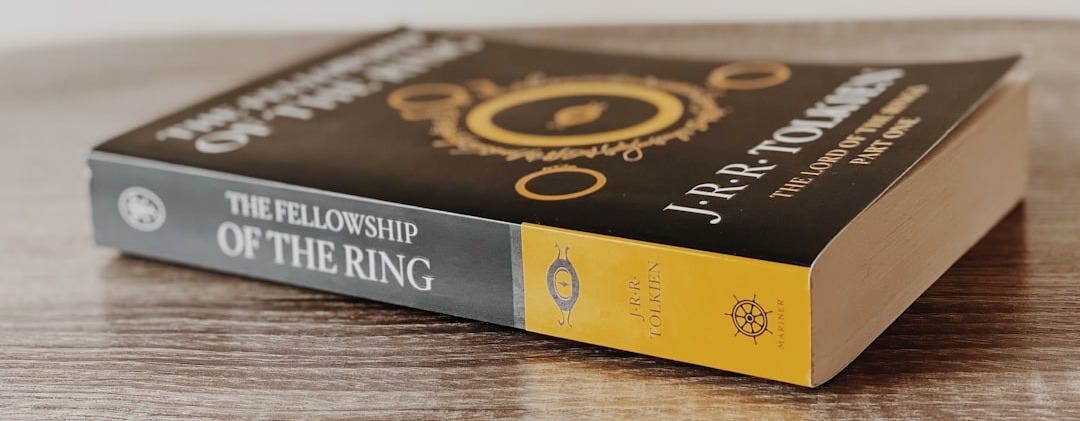

I’ve given up hope a few times, like I said. I’ve thought, “Maybe fantasy is just for kids, and maybe I should only be interested in realism now that I’m a grown-up.” Yet I keep coming back to Tolkien and Lewis (and a handful of others)--and then I wonder, “What else is out there?” and I read Rothfuss, Martin, Pullman, and Grossman to get a taste of the more recent offerings of the fantasy market. My stomach twists. Spectacle and scintillation are fool’s gold, but this belies the real hunger for true gold.

Too often power fantasies leave me cold and bitter because I can’t root for any of their small, acid, shallow, greedy heroes, or because the good men and women in the story get killed off because “That’s life, folks. Suck it up.”

But I must push past my misgivings and grasp at the wonder, the power of the stories I love. There is a hazy reason I haven’t given up on it, even now that I’m a husband, father, professional, and committed churchman. It would be easy to give up, to walk away into the usual suspects of wasting time or soul-mashing hobbies. But I have a plan to fight for this love, this Tolkienian sub-creation, this Lewisian clarity of thought.

Since Tolkien and Lewis in the mid 1900s, few have risen to take the mantle of fantasy master storytellers. Plenty have aped but few have captured the masters’ essence. It seems that the genre has abandoned the work of greatness, trading it instead for a thin soup of outlandish, ornery otherness.

So the task is to find that kernel of greatness and let it go to seed and leaf, because, like Tolkien and Lewis, I find that the stories I like to read aren’t being written so I must write my own. After many years, I think I have settled what the missing, threefold kernel of masterful fantasy is: timelessness, selective excellence and hopecraft. Each leads into the next.

By timelessness, I mean not chasing trends or tropes and instead writing the story. A story has a beginning, a middle, and an end, and change is the ingredient that makes it all work. It speaks to the human plight, which doesn’t change no matter if we’ve got a stone in our pocket or an iPhone, no matter if we’re driving a mule or a Tesla. Language and diction changes throughout the centuries, but story itself doesn’t. The masters tap into and copy the old tales, because the old tales tapped into and copied older tales. Worn out, dragging stories don’t fail because they’re not current enough but because they’re too hasty. Timelessness is achieved by wise choosing of subject matter.

By selective excellence I mean the usual kind of writing advice that is given lip-service but not followed enough: kill your darlings (unfitting or lackluster thoughts, not mere favorite characters), edit so that only the best stuff is left, and understand the true power of story. This involves being discriminating in the best sense of the word. This means not churning out “content” but striving to make the tale the best it can be (otherwise why write it?). And the most excellent stories lift up their readers.

By hopecraft I mean the brave exercising of faithful hope and having the brashness to lean on a thesis. The best stories balk against defeatism and sophomoric skepticism. If nothing really matters, your story doesn’t either. I mentioned before that I like a foray into Lovecraft from time to time, but wading through such despair and fear is no way to live. Hopelessness always sours the stories, because as intriguing as the Cthulhu Mythos can be, the stories spell no future. It may be cathartic to duck into a shallow, dank cave from time to time, but we live in the sunlight. If we are living for upright and bright ends, our stories should be dripping and drenched in hope.

By hopecraft I mean the brave exercising of faithful hope and having the brashness to lean on a thesis... If we are living for upright and bright ends, our stories should be dripping and drenched in hope.

This is no theological justification for hope, nor is it an academic treatise on how story works. These are my mere thoughts. I plan to develop them further in coming days.